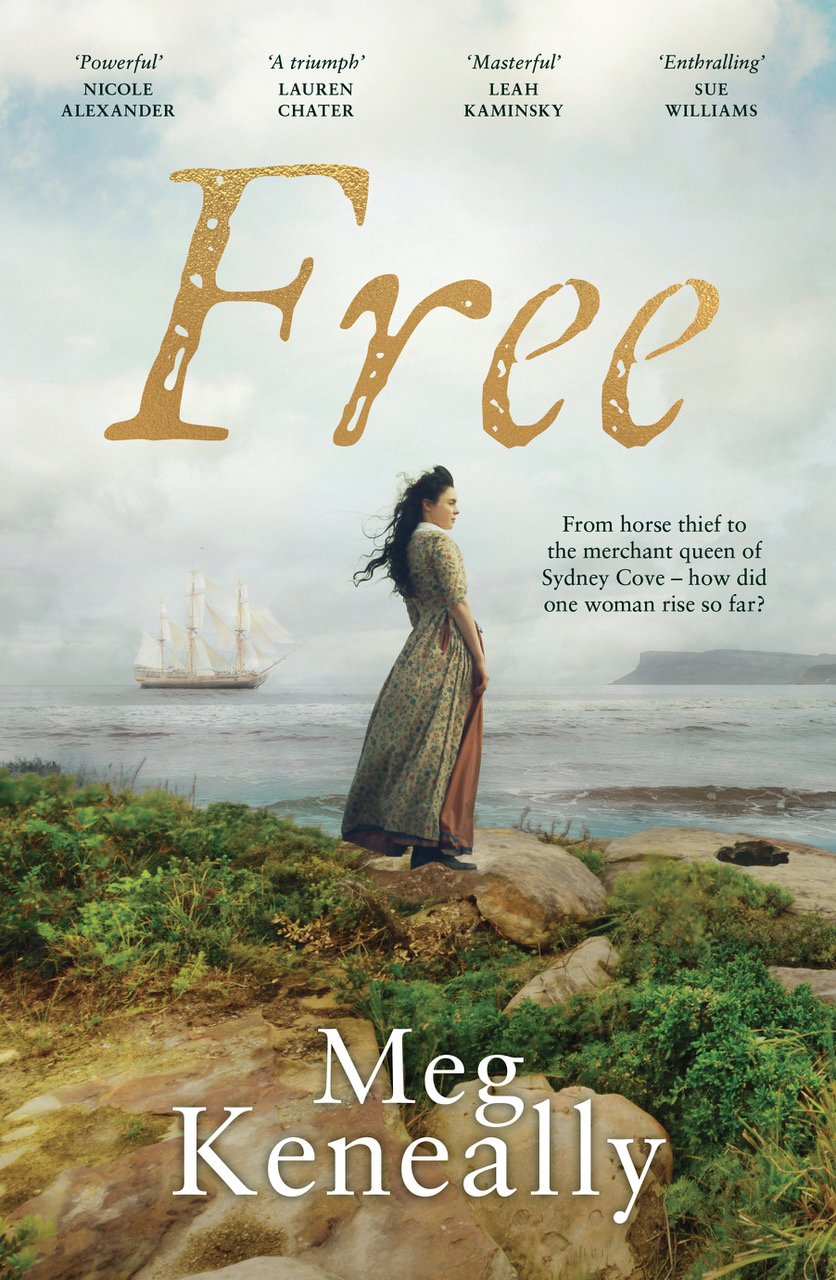

Start reading Free by Meg Keneally

Chapter One

Bury, Lancashire, 1789

The palm of his hand connected with the middle of her chest and she was on the ground, mud soaking into her skirts. She must remember not to stand near a puddle when she playfully called James a coward. Still, this escapade was nearly worth the inevitable scolding.

‘You have lost your wits if you think I am going to ride that horse,’ James said as Molly rose from the puddle and began to

wring out her skirts. ‘Considering who owns her.’

‘You haven’t been listening in church, James. Don’t you know all God’s creatures are free?’

‘That horse isn’t,’ James said. ‘Least, not as far as Rutherford is concerned.’

They were standing at the edge of a pasture. Nearby, ignoring them while she cropped grass and let out the occasional contented whinny, was a bay mare.

Most of the males Molly knew, and James especially, were wiry rather than muscular. So was she – she’d lugged enough firewood in her time and carried bags full of laundry, pails of water. The creature in the field, though, was different. Hard to believe she was the same type of animal as the cart horses that trudged the same streets as Molly, with their bones visible under the skin of their haunches.

Whenever Molly passed this particular patch of grass, she would stand and stare at the mare’s chest, at the bulges of muscle under the sleek brown hair. She reckoned this animal was probably the strongest creature she had ever seen. And unlike the average cart horse, which flinched on occasion when approached, this girl had no need to fear a human voice. She was the pride of Mr Rutherford, the local magistrate, who would ride her sedately through the streets of Bury pretending not to be aware of the envious glances.

Molly had once squeezed herself under the fence at the edge of the pasture. She had wanted to put her hand on the chest, find out whether the mare’s muscles were as pillowy as they looked.

She had never ridden a horse, although she dimly remembered her father lifting her onto one of the cart horses, holding her as she giggled and bounced. Molly couldn’t quite remember what her father looked like now. She remembered his hands, though, under her arms, hoisting her up. His cackle, which matched her giggles. The feel of his whiskers under her hands when he lifted her onto his shoulders and she looped her arms around his neck.

So when her grandmother told her she was just like him, she wasn’t sure what the old woman meant. She was fairly certain, though, that it wasn’t intended as a compliment. ‘He would have ended on one of them boats,’ Mrs Darrow – as Molly Darrow was required to address her grandmother – would say.

Molly knew which boats she meant. They did, on occasion, travel the nine miles to Manchester where her grandmother would take her to the river, standing on the bank with the little girl who had been foisted onto her and looking at the strange squat ships that weren’t ships, their masts lopped off like a soldier’s arm. It was an ignoble end for a once proud vessel, forever at anchor, used to hold the prisoners who would not fit in the gaols on land.

‘Hatches are closed, see?’ she would say, pointing. ‘Hatches are closed. Why do you think that is?’

‘They don’t want them to escape?’

‘They stink too badly. Decent people don’t need to be smelling it.’

Sometimes Molly looked at her grandmother’s face when the old woman wasn’t aware, nodding by the fire, needlework forgotten in her lap. There was still a hint of the softness Molly remembered, the sad smile of the woman who had lifted her from the edge of her father’s grave and brought her to the safety of her hearth. There was an almost imperceptible hardening the first time Molly returned to her grandmother’s home with a torn skirt after a misadventure involving a fence that was begging to be scaled. Over time, that softness coagulated into something new, a landscape of frowns and pursed lips accentuated by every transgression, every failure, every outright refusal to fold one’s hands in one’s lap, to scrub the floor, to tend the fire.

If only she could be like Nancy. Nancy was perfect. Or, at least, everyone thought she was. Molly’s cousin always walked straight, her shoulders back, a calm smile on her face. She never acknowledged the ungentlemanly invitations that had been proffered on occasion since her fifteenth birthday

when her shape filled out. She had mastered the inoffensive response, the conversation that touched on seemingly everything but nothing of substance.

Nancy was the kind of girl Molly would have hated if she had been as perfect as she seemed. Instead, she was the only person who approved of Molly’s adventures. She would take her younger cousin for a walk under the guise of teaching her some manners and breathlessly ask for details.

‘How do you stop them looking up your skirt when you climb a tree?’

‘Caught someone doing it once. Broke off a branch and let it drop, hit him right in the eye. They didn’t try it again, any of them.’

Nancy would emit a snort that Molly was certain the girl’s parents had never heard.

Over the years, Molly had asked whether she could live with Nancy and her parents. But her uncle and aunt, the latter being the sister of Molly’s mother, whose life had been taken by her birth, claimed a lack of space, with five younger children coming up behind Nancy.

Molly had even tried to convert her grandmother to her cause. ‘If I lived there, I’m sure some of her manners would rub off on me,’ she said.

‘If they haven’t by now, they never will,’ her grandmother had said.

‘How do you manage it?’ Molly asked on one of their walks. ‘How do you fool them?’

‘It’s a game, and I enjoy it,’ Nancy said, ‘seeing how comprehensively I can make them believe I am a paragon. It’s ridiculously easy.’

Not for me, thought Molly.

She should feel bad, she supposed. Terrible. There was an imp in her that tickled her feet and twitched her muscles and prevented her from sitting still and quiet. Instruction, it was called, when the old lady took the switch from behind the door and flicked it against Molly’s back. James, she knew, took a similar treatment to his bare buttocks, but her grandmother would never countenance such immodesty.

She did wonder what the point of this instruction was. If you were being instructed, there should be some hope of something to learn. But Grandmother frequently declared that Molly was beyond help, so why continue these lessons at the end of a switch?

There was a time when the old woman’s papery rasp had slithered into Molly’s ear and wrapped itself around her throat, her chest.

The voice, though. The mix of outrage and despair. The words that asked her to be something she couldn’t be, the incomprehension that she could no more please her grandmother than fly. She would stand the other end of a scolding and snake her hand up behind her neck, digging her nails into her skin until the pain drowned out the words.

Over time she had taught herself to hear without listening, to pick out the words that heralded a practical instruction – go, do – as she had no desire to walk away from a request to fetch water, although her grandmother would easily think her capable of it. The rest of the words skated over her awareness, flying past her ears and out the door.

So she couldn’t, under threat of torture, tell anyone what her grandmother had said to her this morning as she left, although she dimly remembered the phrase ‘that boy’ following her out the door.

He was something of a puzzle to her, James. A visitor to the world rather than a resident. It seemed he could close down his senses so that cruel words bounced off him. She had seen him once take a beating from the vicar when he had fidgeted too much during service. He had barely flinched. She wanted to ask whether any of it penetrated, whether he had truly mastered the ability to shield himself from the world, whether his skin was made of iron. But he didn’t like personal questions. On occasion, when she asked one, he would punch her in the arm and run away.

Most of the time, though, he was happy to be dragged along on one escapade or another. And he, like her, was a big admirer of the bay mare. But even James wasn’t immune to the occasional bout of male pride.

‘I’ve ridden her,’ she said.

‘You have not!’

‘I have! Last Sunday morning, just as it was getting light. I climbed on the fence there, see? She was about where she is now, right next to me, so I hopped on her back and she took off. Seemed to be enjoying it. Likes a bit of company, I expect.’

‘She can like it all she wants, she is not getting any company from me.’

‘Don’t worry, it’s not hard. You just need to hang on around her neck.’

‘I’m not saying it’s hard!’

Molly stepped back. James rarely yelled. She enjoyed needling him in the same way she enjoyed tugging on one end of a rope held in the mouth of a dog: if the dog had whimpered, she would have stopped.

‘You’re right,’ she said. ‘I know you’re not. It’s all right, you don’t have to.’

He glowered at her and walked over to the fence.

The mare lifted her head slightly, sparing him a brief glance, mildly annoyed that her meal had been interrupted.

James climbed the wooden slats of the fence, one of them breaking under his weight. He looked back at Molly, his face suddenly drained, white. He tightened his jaw and made an awkward but effective sideways lunge, vaulting himself onto the back of the horse. He tried to circle her neck with his arms, but they couldn’t quite reach.

So he grabbed her mane instead.

He wouldn’t have meant to cause the horse pain, but he must have tugged a little too hard. In one fluid motion, the mare went from nose down in the grass to rearing, her hooves scratching at nothing before coming down to the ground again with a thud, and she galloped off. James only managed to hold on for a few seconds until the mare gave another buck and he slid off, falling to the grass with a thud.

Molly scrambled over the fence and ran towards him, not even turning when she heard a shout from the other end of the field and the sound of pounding feet. She reached James first where he still lay face down. ‘We have to go,’ she told him, grabbing his shoulder to turn him over. ‘We’ll get in trouble.’

His face, now pointed at the sky, was as white as it had been when she had seen it just a few moments ago. When he had been breathing. The fear that she’d seen in his eyes, though, was no longer there. Just an absence, white and grey glass reflecting the clouds back at themselves, while a single crimson red lick ran down from his ear.

‘Boy!’

Two men were running. One veered off to the side. He had a rope in his hand, trying to throw it around the neck of the horse, which was still rising and plunging.

The other, wearing the livery of a servant, was closing quickly. She stood and stared at him, her mouth open, her cheeks wet. He stopped for a moment, looked from her to the prone form on the grass, and she saw his hair catch the sun, a shade of white-blond she knew many girls would covet.

‘It’s a girl, not a boy,’ he yelled to the other man. He spat and began running again.

She tumbled over the fence and into the forest before he reached her, then heard him stamping around and calling, ‘Come out!’ His heart didn’t seem to be in the chase, though, and after a little while she heard the crunching of leaves under his feet get fainter. He had given up on her.

She didn’t blame him.

Free by Meg Keneally

From horse thief to the merchant queen of Sydney Cove – how did one woman rise so far?